I have lived in Wales for more than twenty years now and, although I am still stumbling upon new treasures, there

are some places that I find myself returning to time and time again. One of my

favourites is Tretower Court. It sits in

the green Usk Valley between Abergavenny and Brecon, seemingly untouched,

timeless.

When compared with the tourist

hot spots like Pembroke and Conwy castles the site is small but this simply

adds to the atmosphere. The noise of the traffic dwindles and all you can hear

is birdsong and the sporadic bleating of sheep. A few years ago Tretower was

little known and I’d find myself the only person there, with the ghosts of the

past whispering in my ear.

Tretower marks the period when

castles were abandoned in favour of more comfortable, less fortified homes. There

are two distinct sites at Tretower, each as valuable in their own way as the

other: the later medieval house and, two hundred yards to the north-west, the

remains of the 12th century castle stronghold, the round tower being added

later in the period.

Although the more domestic Court

building was erected early in the fourteenth century, later additions to the

Tower suggest that the stronghold was not entirely abandoned at this time.

Should the house have come under attack the inhabitants would simply gather up

their possessions, round up the livestock, and take cover behind the

impregnable walls of the tower.

The earliest part of medieval

house is the north range, which dates from the early fourteenth century. The

masonry and latrine turret on the west end may even have been built as early as

1300. The four major phases of building can clearly be seen from the central

courtyard as can the later modifications added as late as the seventeenth

century. As you move from room to room, duck through low doorways, climb

twisting stairways and creep into the dark recesses of the latrine turrets you are

not alone. So much has happened here, so many people have passed through, so

much laughter has rung out and so many tears have fallen. It is a jewel for any

writer, I can smell the stories still waiting to be told.

A motte and bailey was raised by

a Norman follower by the name of Picard. The property passed through the

family’s male line until the fourteenth century when it moved, via the female

line, to Ralph Bluet and then, again through the marriage of another daughter,

to James de Berkeley.

His son, also James, became Lord

Berkeley on the death of his uncle. Tretower was later purchased from James by

his mother’s husband, Sir William ap Thomas. Sir William’s second wife,

Gwladys, gave him a son, William Herbert, later the earl of Pembroke, who

inherited both Tretower and Raglan Castle on his father’s death. Tretower was

later gifted to William’s half-brother, Roger Vaughan the younger, around 1450.

Herbert and Vaughan both played important

roles during the Wars of the Roses. William Herbert was both friend and advisor

to Edward IV and his career prospered until 1469 when he was executed following

the Yorkist defeat at Edgecote.

Roger Vaughan, who was

responsible for most of the major reconstruction of Tretower Court, was

knighted in 1464, and present as a veteran at Tewkesbury and finally captured

at Chepstow. There, he was executed by Jasper Tudor in an act of vengeance for

beheading his father, Owen Tudor, ten years previously. Tretower remained in

the possession of the Vaughans until the eighteenth century when it was sold

and became a farm.

Years of neglect and disrepair

followed and it was not until the twentieth century that preservation and

repair work began. The reconstructions at Tretower

are beautifully done, the living history displays that take place there

providing deeper knowledge of how the dwelling was utilised.

The garden with its relaxed

medieval planting is as beautiful as any I have seen is this country. Laid out

and designed by Francesca Kay, it has a covered walk way, tumbling with red and

white roses, fragrant lavender, aquilega, foxgloves and marigold sprawl beside

a bubbling fountain in the midst of a chequered lawn.

I spent a long time here on a warm

Sunday morning in July, wandering through the rose arbour, lingering in the

orchard before returning to the house. As I progressed along the dim corridors

I could almost hear the skirts of my gown trailing after me on the stone

floors. I paused, and time was suspended as I looked through thick, green glass

to the courtyard and garden below.

If you ever have the good fortune to visit

Wales, make the time to call in at Tretower and don't forget to bring a picnic

and a blanket for I guarantee you will want to linger.

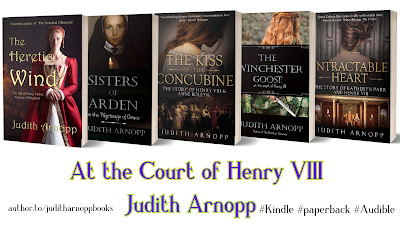

More information about Judith Arnopp and her

books can be found on her website:

http://www.judithmarnopp.com

or her author page author.to/juditharnoppbooks