|

| The Hever Portrait |

The subject to Anne Boleyn’s

true physical appearance has been discussed time and time again in books, blogs

and journals, yet it is a subject that remains endlessly fascinating, the

varied opinions and theories almost as intriguing as the woman herself.

Almost instantly recognisable,

Anne Boleyn’s portrait graces thousands of book covers, mugs, tea towels, key

rings…her face is everywhere. But is it really her face that we are seeing? Do

the portraits show us what was Anne really like?

I don’t intend to hold a full

debate on the portraits here but none we have are contemporary and the

closest are copies made of likenesses

painted in her life time.

After her execution it wasn’t

wise to have representations of a fallen queen gracing one’s walls so during

the remainder of Henry’s reign and the years of Edward and Mary’s rule, her

face and many artefacts belonging to her, slipped away. It wasn’t until her

daughter, Elizabeth, ascended the throne that Anne became acceptable again and

the demand for her image increased. As a consequence most extant images were

worked long after her death – some as late as the 17th century.

The likenesses attributed to be

her range from softly pretty to plum ugly as do the textual descriptions.

Opinions of Anne Boleyn depended enormously upon the political stance and

agenda of the author and as a consequence the documentary evidence is as varied

and unreliable as the pictorial.

Due to her efforts for

religious reform and the displacement of Catherine of Aragon, Anne was never a

favourite of Spain or the Catholic faction and this is clear from some of the

descriptions of her. Roman Catholic Nicholas Sander saw her as: ‘…rather tall

of stature, with black hair and an oval face of sallow complexion, as if

troubled with jaundice. She had a projecting tooth under the upper lip, and on

her right hand, six fingers. There was a large wen under her chin, and

therefore to hide its ugliness, she wore a high dress covering her throat. In

this she was followed by the ladies of the court, who also wore high dresses,

having before been in the habit of leaving their necks and the upper portion of

their persons uncovered. She was handsome to look at, with a pretty mouth.’

Very nice of him to go to the

trouble of saying so. And the Venetian ambassador was scarcely more flattering

in his account.

‘Madame Anne is not one of the

handsomest women in the world. She is of middling stature, swarthy complexion,

long neck, wide mouth, bosom not much raised, and in fact has nothing but the

King's great appetite, and her eyes, which are black and beautiful - and take great

effect on those who served the Queen when she was on the throne. She lives like

a queen, and the King accompanies her to Mass - and everywhere.’

It is quite clear that she was

not a ravishing beauty although of course, what is considered beautiful today

is vastly different to that favoured in the 16th century. If you look at the

line-up of Henry’s wives, the ‘Flanders Mare’ of Henry’s stable, Anne of

Cleves, was by today’s standards, rather pretty.

In a society that favoured

delicately complexioned blondes, Anne’s dark hair and olive skin were far from

fashionable and neither did her slim, small breasted (‘not much raised’) figure

fit the current vogue for voluptuous women.

But most descriptions, even the

most unfavourable, agree that Anne possessed expressive eyes and a vivacious

wit and it must have been those attributes that captivated the king. Which, for

once I think, speaks rather well of

Henry in that he was able to see past contemporary ideals to what lay beneath.

Shame it didn’t last.

The only truly contemporary

image we have of Anne is a badly damaged portrait medal that nevertheless bears

some resemblance to the Anne we see depicted in later portraits. From this we can deduce that we can come

quite close to discovering a likeness to the real woman.

The medal was struck in 1534

with Anne’s motto, ‘The Most Happi’ and the initials ‘A.R’ – Anna Regina, so we

can be quite sure that it is her. These medals were usually struck to

commemorate a great event, often a coronation but since the date does not tie

in with this, Eric Ives believes that it was more likely to have been intended

to mark birth of Anne’s second child in the autumn of 1534 that she miscarried.

This theory also explains why few copies survive.

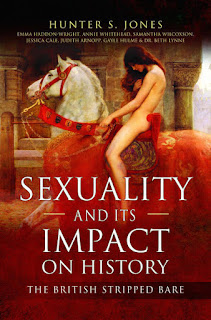

Other portraits include the

familiar Hever portrait and the one at the National Portrait Gallery as well as

some sketches by Holbein which receive varying degrees of certainty from the

experts. The Nidd Hall portrait shows an aging Anne which is closer to some of

the less favourable documented descriptions discussed previously. Another

rather touching artefact is the Chequers Ring, a jewel removed from the finger

of Elizabeth I on her death bed and found to contain the image of herself and

her mother, Anne.

Of course, we can never know the

extent of Elizabeth’s attachment to her mother but some documented incidents

point to a curiosity about her. Although Elizabeth was just two years old when

Anne was executed and is not likely to have had strong memories of her, there

were those around her who had known Anne and would have been able to keep her

memory alive. If Elizabeth was satisfied that the image bore a likeness to her

mother then I think we can be fairly confident too.

The recent (and not so recent)

discussions of Anne’s appearance have led to the assumption that she and her

daughter bore a close resemblance. Apart from Elizabeth’s colouring which was

auburn and Tudor in origin, there are likenesses to Anne, especially in the

earlier portraits before Royal iconography began to overshadow Elizabeth’s

personality. The dark eyes are particularly similar.

I spend a lot of time looking

at paintings of historical figures and it has always struck me that in later

life Elizabeth closely resembled her great grandmother. I suppose it should

come as no surprise that there is also a look of Henry VII, Elizabeth’s

grandfather. Perhaps there is more Tudor

in Elizabeth than we thought.

The Kiss of the Concubine: a story

of Anne Boleyn is now available in paperback, kindle and also as an audiobook.

To celebrate the new audio format I have a few FREE codes for audible members.

You can also use it to make your first purchase when you take out a FREE three

month trial of audible.

Contact me via messenger or

email for FREE Codes.